Invocation

Lord Ganapathi

Lord Muruga

Abstract

Introduction

The Yazidis

-

Figure 1: Peacock Angel of Yazidis (Source: Ezidi shrine of Sharaf al-Deen nestled into the Shingal mountains near Sinune village 06 - Tawûsî Melek - Wikipedia)

- (a) Ezidi shrine of Sharaf al-Deen nestled into the Shingal mountains near Sinune village

- (b) Melek Taûs, the Peacock Angel

- (c) Melek Taus, the peaclcik angel. This emblem feaurs Tawusi Melek in th center, the Sumerian digir on the left, and the domes Sheik ‘Adi’s’ tomb on the right

Religion

- Beliefs: Yazidism is a monotheistic religion that incorporates elements of Zoroastrianism, Islam, Christianity, and ancient Mesopotamian religions. It is unique and distinct from these faiths but shares similarities in some practices and beliefs.

- Sacred Texts: Their sacred texts include the Kitêba Cilwe (Book of Revelation) and the Mishefa Reş (Black Book).

- Central Figure: Yazidis revere Melek Taus, the Peacock Angel, as a central figure in their faith. They believe Melek Taus serves as a mediator between God and humanity.

- Spiritual Practices: The Yazidis have a rich tradition of oral literature, sacred hymns, and rituals tied to nature and their cultural heritage.

Culture

- Kurmanji Dialect: Yazidis primarily speak Kurmanji, a northern Kurdish dialect. It serves as a key element of their cultural identity.

- Cultural Practices: Yazidis have a rich cultural history, with unique traditions, music, and dances integral to their community and religious ceremonies.

Community and Resilience

- Diaspora: Due to historical persecution, there are Yazidi diaspora communities worldwide, particularly in Germany, which has one of the largest Yazidi populations outside of the Middle East.

- Survival: Despite challenges, Yazidis have shown remarkable resilience, striving to preserve their cultural and religious identity while advocating for justice and recognition for the atrocities committed against them.

- Oral Tradition: Yazidi culture is deeply rooted in oral literature, including hymns, stories, and poetry, which are transmitted through generations by religious leaders and community elders.

Traditional Practices

Festivals and Celebrations:

- The New Year (Sere Sal): Celebrated in April, it is one of their most important holidays, marked by decorating eggs and lighting lamps.

- The Feast of the Assembly (Cejna Cemaiya): Held in autumn at Lalish, their holiest site, it includes prayers, rituals, and communal gatherings.

- Ezi Day: A festival honoring their religious figure Sultan Ezid, often involving fasting and feasting.

Arts and Music

- Music: Music plays a vital role in rituals and storytelling. The Qewals, religious singers, preserve Yazidi hymns and prayers.

- Dance: Traditional dances are part of their festivals and ceremonies, reflecting communal joy and spirituality.

Cuisine

- Staples: Yazidi cuisine includes grains, vegetables, and dairy. Dishes like dolma (stuffed grape leaves) and flatbreads are common.

- Hospitality: Sharing meals is a vital aspect of Yazidi culture, reflecting their sense of community.

History

- Origins: Yazidism is believed to be an ancient faith with roots in pre-Islamic Mesopotamian religions, possibly dating back thousands of years. It integrates influences from Zoroastrianism, Mithraism, and ancient Assyrian beliefs.

- Medieval Period: During the Islamic caliphates, Yazidis faced periods of coexistence but also persecution for their distinct religious beliefs. Misinterpretations of their veneration of Melek Taus led to accusations of "devil worship." Many Yazidis fled to the mountains or became refugees. Survivors advocate for recognition of the genocide and justice for the atrocities.

- Diaspora: Displacement from their homeland has led to large Yazidi communities in Europe, particularly in Germany, where they continue to preserve their identity and culture.

Melek Taus (The Peacock Angel):

Sacred Sites

- Lalish: Located in northern Iraq, it is the holiest site for Yazidis. Pilgrimage to Lalish is a key religious obligation.

- Shrines: Numerous shrines dedicated to saints and religious figures dot the Yazidi homeland.

Religious Texts

Spiritual Leaders

- Sheikhs and Pirs: Spiritual leaders responsible for guiding the community and conducting rituals.

- Mirs: The hereditary leaders of the Yazidi community.

Rituals and Practices

- Prayer: Yazidis pray facing the sun, acknowledging its life-giving power.

- Purity and Taboo: Ritual purity is central to Yazidi practices, and certain foods or colors (e.g., blue) are considered taboo.

- Baptism: Performed at Lalish, it is a significant rite of passage.

Challenges and Resilience

Mythology and Cosmology

Creation of the World

Role of Melek Taus

The Sacred Peacock

Sacred Symbols

- The Sun: Worship of the sun is integral to Yazidi practice, symbolizing the light of God.

- The Snake: In Yazidi tradition, the snake is a protector, unlike its representation in some Abrahamic traditions.

- Figure 4: Engraved symbols on the walls of Yazidis Sun Temple (source: https://kirkuknow.com/en/news/63175)

- Figure 5: Lalish Temple in Duhok Province (Source: https://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/270120231)

- Figure 6: Yazidis Religious temple – Sun symbol (Source https://informacionpublica.svet.gob.gt/el-filibusterismo-kabanata-16/el-filibusterismo-kabanata-16/yazidi-religious-symbol-dome-yazidi-temple-ziarat-armenia-village-mm-eQ3rmJT2)

Social Structure

Caste System

- Mirids (Commoners): The majority of the Yazidi population. They engage in agriculture, trade, and other professions.

- Sheikhs: Spiritual leaders who guide the religious practices of the community.

- Pirs: Religious scholars and advisors.

- Mir: The highest religious and community leader, responsible for maintaining traditions and representing the Yazidis.

Rules and Customs

- Endogamy: Marriages must occur within the Yazidi community and caste.

- Taboos: Interaction with outsiders is historically restricted to preserve the purity of their faith. Conversion into or out of Yazidism is not permitted.

Role of Women

Cultural Preservation

- Education: Yazidis are focusing on educating the younger generation about their history and traditions.

- Documentation: Efforts to record oral histories and sacred hymns have intensified to ensure their survival.

- Advocacy: Yazidi leaders, including Nadia Murad, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, have brought global attention to their community’s plight.

Yazidi Mythology: Deeper Insights

Seven Holy Beings

- God entrusted the care of the universe to seven angels, led by Melek Taus.

- These beings are intermediaries between God and humanity, ensuring harmony in the cosmos.

Creation of Adam and Eve

The Peacock Angel

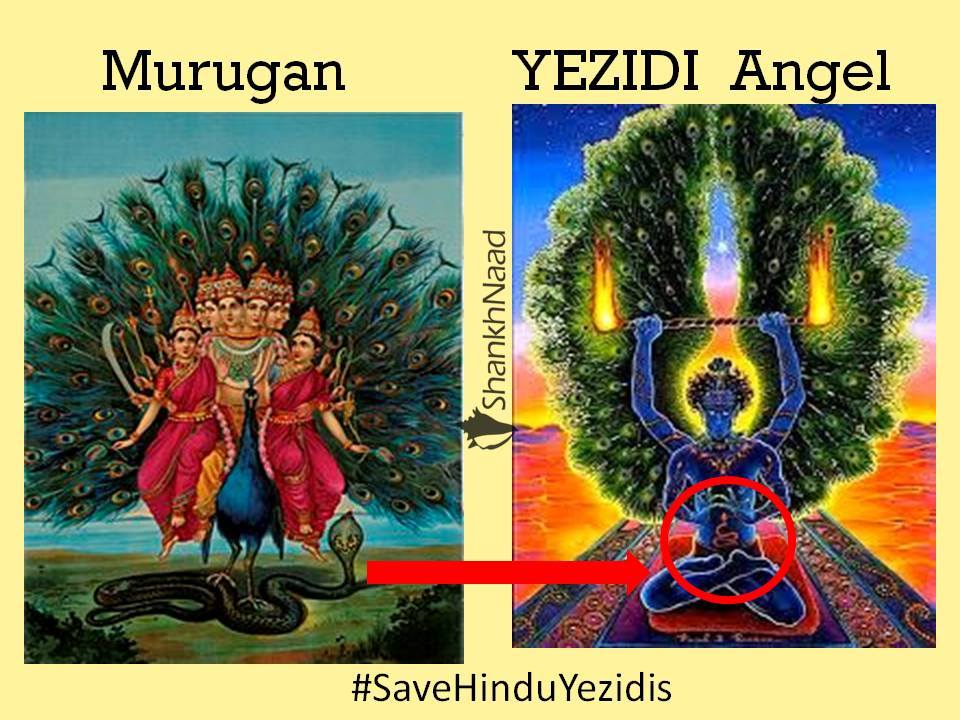

- Figure 7: Murugan and Yazidi’s angel (Source:https://yavuztellioglu.blogspot.com/2015/08/melek-taus-tawuse-melek.html)

- Figure 8: The Snake: In Yazidi tradition, the snake is a protector, unlike its representation in some Abrahamic traditions. (Source: https://kirkuknow.com/en/news/63175)

The Role of Lalish

Notable Figures: Nadia Murad

Who is Nadia Murad?

Survivor to Advocate

Contributions

- Advocacy: Nadia founded the Nadia’s Initiative, an organization dedicated to rebuilding communities in crisis and advocating for Yazidis.

- Memoir: Her book, The Last Girl: My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State, documents her harrowing experiences and calls for global action.

- Global Recognition: By winning the Nobel Peace Prize, Nadia brought unparalleled attention to the plight of Yazidi women and the genocide.

Future Directions for Yazidis

- Reconstruction of Sinjar: Rebuilding infrastructure, homes, and sacred sites in Sinjar is a top priority.

- Education and Preservation: Younger generations are being educated in Yazidi traditions and history, both in the homeland and diaspora.

- Advocacy for Rights: Leaders and activists are pushing for legal recognition of the genocide and reparations for survivors.

- Global Solidarity: Partnerships with international organizations aim to ensure long-term support for Yazidis.

Yazidi Traditions

Religious Practices

Pilgrimage to Lalish:

Fasting:

Celebrations:

- Sere Sal (New Year): Celebrated in April, it involves decorating eggs and lighting lamps to symbolize renewal.

- Feast of the Assembly (Cejna Cemaiya): A week-long gathering at Lalish with prayers, music, and communal meals.

Cultural Taboos

Purity Rules:

Endogamy:

Art and Music

Sacred Hymns (Qewls):

- Passed down orally, these hymns narrate Yazidi myths and prayers.

- They are performed by Qewals, religious singers who play the tambour and flute during ceremonies.

Dance and Festivities:

Cultural Preservation

Educational Initiatives

Similarities Between Yazidi Worship and the Worship of Lord Subramanya

1. The Peacock as a Sacred Symbol

- The peacock represents Melek Taus, the Peacock Angel, who is the central figure of Yazidi theology. He embodies divine wisdom, light, and beauty.

- Melek Taus is often depicted in their hymns and ceremonies as a radiant being associated with cosmic order and guidance.

2. Lamp Lighting

- Yazidis: Lighting oil lamps is a central ritual in Yazidi temples, especially at Lalish, their holiest site. The lamps symbolize enlightenment, divine guidance, and the eternal presence of God. Lamps are lit during festivals like the Feast of the Assembly and the New Year.

- Hinduism: In Hindu temples, lighting oil lamps (often called deepam) is a daily ritual. It signifies the removal of darkness (ignorance) and the welcoming of divine knowledge. Special occasions, like Kartikeya festivals, often feature large lamp-lighting ceremonies.

3. Snake Motifs

- Yazidis: Snakes are seen as protectors in Yazidi mythology. A black snake is said to have saved the Yazidi people by sealing the entrance of Lalish when they were under threat. Snake motifs are sometimes found in Yazidi sacred art and oral traditions.

- Hinduism: Snakes (Nagas) are revered in Hindu traditions, particularly in the worship of Lord Subramanya. They symbolize fertility, protection, and the cyclical nature of life. Snake worship is prominent in Subramanya temples, where they are often depicted in carvings or represented by stone idols.

Comparison of Yazidi Temple Architecture and Hindu Subramanya Temples

Yazidi Temples (Lalish)

- Every architectural element represents spiritual concepts, such as the domes symbolizing the cosmic egg.

- The temple's natural setting reinforces Yazidi connections to the earth and the cosmos.

Hindu Subramanya Temples (e.g., Palani, Tiruchendur)

- The peacock, snake, and vel (spear) are central motifs in temple architecture.

- The temple's design aligns with Vastu Shastra principles, emphasizing cosmic harmony.

Key Comparisons

| Aspect | Yazidi Temples | Hindu Subramanya Temples |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Symbol | Peacock (Melek Taus) | Peacock (Lord Subramanya’s vahana) |

| Sacred Ritual | Lighting oil lamps | Lighting deepams |

| Snake Symbolism | Protector in mythology | Fertility and protection |

| Temple Setting | Remote, natural sites (e.g., Lalish) | Hills and seashores (e.g., Palani, Tiruchendur) |

| Architectural Style | Simple, cone-shaped domes | Ornate gopurams, garbha griha, and mandapas |

| Water Features | Sacred springs | Tanks or nearby rivers for ablution |

Philosophical Parallels

4. Temple Comparison: Side-by-Side

| Aspect | Yazidi Temple (Lalish) | Hindu Subramanya Temple (e.g., Palani) |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Remote mountainous regions | Hilltops or coastal areas |

| Primary Symbols | Peacock (Melek Taus), Snake, Sun | Peacock (Vahana), Snake (Naga), Vel |

| Lamp Ritual | Oil lamps during pilgrimages | Deepam during daily worship and festivals |

| Architectural Style | Simple, natural stone, conical domes | Ornate, grand gopurams, mandapas, and sanctums |

| Purpose of Water | Sacred springs for purification | Temple tanks and rivers for ablutions |

Significance of Baba Sheikh Khurto Hajji Ismail, the spiritual leader of the Yazidi community, visited the Murugan Temple of North America in Washington, D.C.

1. Oral Transmission of Sacred Knowledge

2. Use of Hymns and Ritual Chants

3. Symbolism of Light and Fire

4. Connection with Nature

5. Moral and Ethical Teachings

Detailed Exploration of Yazidi Music, Instruments, and Dance

1. Yazidi Music

Role of Music in Yazidi Culture

Key Characteristics of Yazidi Music

- Spiritual Focus: Music accompanies prayers and rituals, creating an atmosphere of devotion and contemplation. Themes in Yazidi music often revolve around creation myths, cosmic harmony, and the virtues of Melek Taus.

- Repetition and Rhythm: Repetitive patterns and rhythmic beats enhance the meditative and spiritual quality of their music.

Traditional Instruments

2. Yazidi Dance

Symbolism in Yazidi Dance

Types of Dance

Structure of Yazidi Dance

3. Key Festivals Featuring Music and Dance

- Feast of the Assembly (Cejna Cemaiya): Held annually at Lalish, this week-long festival is the most important Yazidi celebration. Music and dance play a central role, with pilgrims participating in rhythmic circle dances and communal singing.

- New Year (Sere Sal): Celebrated in April, it involves decorating homes with flowers, lighting oil lamps, and performing joyful dances. The festivities mark renewal and the beginning of a new cycle, with music and dance reflecting themes of hope and harmony. Music and dance during the celebrations express gratitude and spiritual devotion.

- Ezi Day: Dedicated to Sultan Ezid, this day involves fasting, prayers, and communal feasting.

4. Connection Between Music, Dance, and Spirituality

Sacred Connection

Preservation of Identity

Comparative Analysis: Yazidi Music, Dance, and Cultural Practices with Similar Traditions

1. Music: Yazidi Hymns and Global Parallels

Yazidi Hymns (Qewls)

Parallels in Other Cultures

- Vedic Chanting (Hindu Tradition): Similar to Yazidi hymns, Vedic hymns are sacred oral traditions passed down for millennia. Chanted in Sanskrit, these hymns are rhythmic and emphasize precise pronunciation, often accompanied by simple instruments like veena or flute during rituals. As an example Rigveda hymns praise cosmic forces like Agni (fire) and Surya (sun), akin to Yazidi hymns celebrating Melek Taus and cosmic harmony.

- Gregorian Chants (Christian Tradition): Performed by choirs or monks, Gregorian chants feature repetitive and meditative tones, much like Yazidi hymns. These chants are unaccompanied and focus on spiritual reflection, similar to the Yazidi Qewls' meditative effect.

- Sufi Qawwali (Islamic Tradition): Sufi Qawwalis are devotional songs that use repetitive verses to create a trance-like state, drawing parallels to Yazidi hymns' spiritual resonance. Instruments like the harmonium and tabla accompany these songs, resembling Yazidi tambour and daf.

2. Dance: Yazidi Circular Dances and Global Comparisons

Yazidi Circular Dances

Parallels in Other Cultures

3. Pilgrimage to Sacred Sites

Yazidi Tradition:

Parallels:

3. Ritual Singing of Hymns (Qewls)

Yazidi Tradition:

Parallels:

4. Use of Sacred Symbols

Yazidi Tradition:

Parallels:

5. Communal Feasts and Celebrations

Yazidi Tradition:

6. Connection to Nature

Yazidi Tradition:

1. Ritual of Lighting Lamps

Yazidi Tradition:

Parallels:

Peacock Symbolism: Yazidi vs. Hindu Traditions

1. In Yazidi Tradition

- Beauty and Harmony: The peacock represents the divine beauty and order of creation.

- Wisdom: Melek Taus is associated with guiding humanity with wisdom and compassion.

- Light: The radiant feathers of the peacock symbolize the illumination of divine knowledge.

- Found in Yazidi art, carvings, and ceremonial objects.

- Incorporated in oral hymns (Qewls), where its vibrant colors are tied to cosmic harmony.

2. In Hindu Tradition

- Victory: The peacock signifies the conquest of ego, ignorance, and evil forces.

- Purity and Grace: Its elegant appearance represents purity and the graceful balance of creation.

- Spiritual Awakening: The peacock’s feathers, adorned with “eyes,” are seen as a metaphor for divine vision and enlightenment.

- Peacock motifs are prominent in Hindu temples, particularly those dedicated to Subramanya (e.g., Palani Temple in Tamil Nadu).

Shared Symbolism

Peacock Symbolism in Other Cultures

1. Christianity

- Symbol: Resurrection and immortality.

- Significance: The peacock’s ability to renew its feathers annually became a symbol of eternal life and resurrection in Christian art.

- Use: Found in early Christian mosaics and church decorations.

2. Persian Tradition

- Symbol: Paradise and divine kingship.

- Significance: The peacock represented grandeur and immortality, often linked to royalty and paradise in Persian art and mythology.

3. Chinese Culture

- Symbol: Dignity, power, and beauty.

- Significance: The peacock is associated with elegance, love, and feminine grace in Chinese art and folklore.